Say What You Mean

As climate change crisis reaches the ‘tipping point,’ scientists are finding it hard to communicate what led to this crisis at the first place and how to combat and adapt to it

By Bhagirath Yogi

The year 2023 was the hottest year on record.

According to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), 2023 was the warmest year on record, with the global average near-surface temperature at 1.45 °Celsius above the pre-industrial level.

People in South Asia are used to heatwaves but ongoing changes in weather patterns are making the lives of local people unbearable.

India recorded more than 40,000 suspected heatstroke cases this summer as a prolonged heatwave killed more than 100 people across the country, while parts of its northeast grappled with floods from heavy rain, Reuters news agency reported quoting authorities.

In North India, temperature soared to almost 50 degrees Celsius in one of the longest heatwave spells recorded.

More than half of all South Asians were affected by one or more climate-related disasters in the last two decades. The changing climate could sharply diminish living conditions for up to 800 million people in a region that already has some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations, The World Bank said.

Over 300 people were killed due to Wayanad landslides in Kerala, India early this year (Photo: PTI)

Tipping Point

According to the British Met Office, in the context of climate science, a tipping point refers to a critical threshold in the earth’s system or related processes which, if passed, can cause sudden, dramatic or even irreversible changes to some of the earth’s largest systems, such as the Antarctic ice sheet or the Amazon rainforest. The resulting socio-economic impacts could be very large, and crossing of one tipping point may then make others more likely to be crossed.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) AR6 Synthesis Report, published in March 2023, highlights that the likelihood and impacts of abrupt and/or irreversible changes in the climate system increase with further global warming. As warming levels increase, so do the risks of species’ extinction or irreversible loss of biodiversity in ecosystems.

So, how do you communicate the crisis to political leaders, lawmakers as well as to the people at the receiving end across the globe?

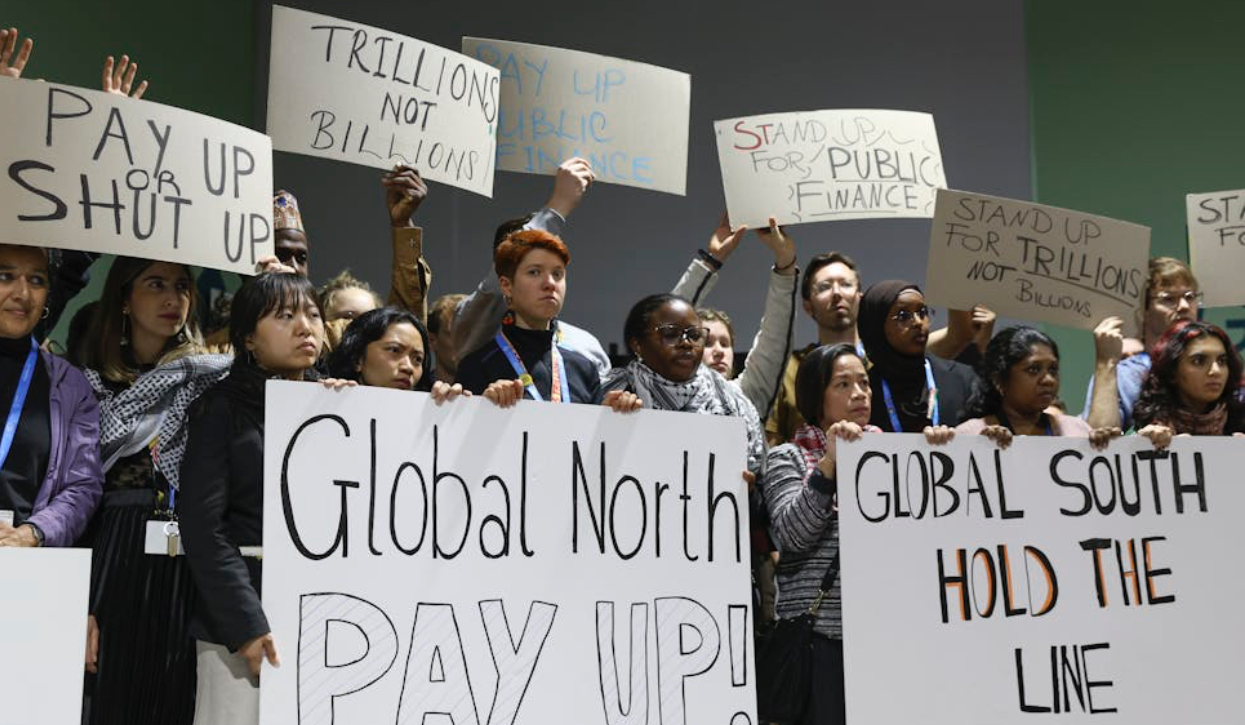

Scientists have found it difficult to explain in plain terms – complex processes that lead to global warming and climate change. While politicians like former US President (and Republican Party candidate) Donald Trump deny or undermine the impact of climate change, their supporters also tend to believe that it’s a political issue rather than a serious stuff. In the wake of challenges like misinformation and disinformation, conveying the latest available scientific knowledge to audiences in a way it prompts them to think, change their behaviour and hold their political leaders to account has never been so urgent as it is today.

In August and September 2023, the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC) conducted an international survey in collaboration with Data for Good at Meta and Rare’s Center for Behavior and the Environment to examine public climate change knowledge, attitudes, policy preferences, and behavior among Facebook users in nearly 200 countries and territories worldwide.

After reading a short description explaining what climate change is, a large majority of men (85%) and women (86%) in low per-capita income/emission countries and territories saidclimate change was happening.

While belief that climate change is happening is generally high, fewer respondents globally understand that it is human-caused. “In low per-capita income/emission countries and territories, 40% of men and 32% of women think that climate change is caused mostly by human activities. By contrast, in high per-capita income/emission countries and territories, higher percentages of both men (45%) and women (46%) think so. Notably, larger proportions of respondents from low income/emission countries and territories incorrectly attribute climate change primarily to natural changes,” the Yale studysaid.

What are the barriers

In a study published in Ghana Journal of Geography last year, researchers including Godfred Osei Boakye et al found that conflicting values and social dilemmas, psychological denial, and the absence of emotional engagement are major barriers affecting the smooth dissemination of climate change-related messages.

After reviewing 100 environmental communication and climate change scientific papers (1990–2022), the study found that mismatch of values between climate message and its audience leads to conflicting values and social dilemmas. Additionally, lack of goal specifications, fear, blaming, and negative criticism also cause psychological denial and the rejection of climate change messages. The study recommended that there is the need for action-directed messages that will identify and resolve specific causes, effects, and outcomes of behaviours causing climate change.

Now the challenge for journalists, press officers and all those who want to convey their message across to masses is how to say exactly what they mean. The guidelines produced by the United Nations Department of Global Communications, in consultation with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), says that reframing the issue to focus on the prospects of a better future can galvanise action.“Addressing climate change will bring about an abundance of opportunities – green jobs, cleaner air, renewable energy, food security, liveable coastal cities, and better health.”

The guidelines further advise communicators to engage theyouth making it clear that the humanity is facing the crisis right now and hence action is also needed now. Similarly, making the message relevant would be equally important. “Limiting global warming to 1.5°C, for example, can be hard for people to relate to. Frame the issue in a way that will resonate with your local audience, by linking it to shared values like family, nature, community, and religion for instance. Safety and stability – protecting what we have – were also found to be highly effective frames for creating a sense of urgency,” the guidelines said.

Suspected glacial collapse damages half of the settlement of Thame in the Everest region (Photo: Nepali Times)

Addressing an event organised by The Royal Society for Arts,Manufacturers and Commerce (RSA) in London in 2019, Amitav Ghosh, an acclaimed Indian writer of nearly 20 books including ‘The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable,’ said that stories we tell can help us understand our place in a drastically changing world. “What we need is to be able to think the unthinkable; if the climate catastrophe we’re facing is a collective failure of imagination as well as one of ethics and action, we need to think beyond the limits of realism to confront the state in which we find ourselves,” said Ghosh adding, “Fiction can be a powerful force for good in helping us to recognise the realities of our condition, and navigate the constant change that defines the modern world.”

From devastating floods hitting Bangladesh to wildfires in Canada, from the Arctic to the Himalayas, there is no place on earth that is immune from the impacts of climate change. People around the world have been telling stories, singing folklores and sharing their experiences in their own language and dialects from generations. What is needed is to listen to their day-to-day concerns, learn from them and tell stories in a way that they can comprehend. Think globally, act locally should be the mantra. But as things stand now time is running out to tell stories of – say the hottest year on record.

(The author is editor-in-chief of www.southasiatime.com and a former BBC World Service journalist based in London.)

Facebook Comments