How debt-for-nature swaps can help create a more resilient South Asia

Last year, Sri Lanka was plunged into economic crisis. As the country struggles in the aftermath of its sovereign debt default in April 2022, officials have said they are considering a debt-for-nature swap. If this happens, this would remove USD 1 billion from Sri Lanka’s outstanding USD 40 billion of debt.

With Ecuador having earlier this month completed the world’s biggest debt-for-nature swap to date, taking roughly USD 1.6 billion off its national debt, these deals look set to play a bigger role in dealing with both debt burdens and biodiversity conservation.

Being home to some of the world’s most important biodiversity hotspots, South Asian countries, several of which are struggling under the weight of their debt, could benefit from these innovative schemes.

How do debt-for-nature swaps work?

A debt-for-nature swap can be multi-party or bilateral. The most common form of multi-party debt-for-nature deal is when a third-party institution – usually an international non-governmental organisation such as Conservation International – buys part of a country’s external debt from the institution that had bought it initially, often at a discount. That organisation then agrees to let the debtor country pay the debt off by investing a certain amount of local currency – usually significantly less than the face value of the original debt – in a biodiversity conservation plan.

In a bilateral deal, a country which owns some of another country’s debt agrees to discount it in exchange for the debtor country investing an agreed amount in a conservation plan. This frees the indebted country from having to pay off some of its debt in US dollars (which international debt is paid in), and it can instead invest its own resources to preserve its biodiversity.

The history of debt-for-nature swaps

The notion of debt-for-nature swaps was first mooted in 1984 by Thomas Lovejoy, the former vice-president for science at the World Wildlife Fund-US, in response to the Latin American debt crisis. The first debt-for-nature swap was a third-party deal facilitated by Conservation International. Finalised in 1987, it involved foreign creditors agreeing forgive USD 650,000 of Bolivia’s debt in exchange for the country setting aside 1.5 million hectares in the Amazon Basin for conservation efforts.

Initially, debt-for-nature swaps were largely offered to Latin American countries, and later to some African countries, Poland, and some countries in the Middle East. These included bilateral debt-for-nature deals accepted by the Paris Club – an informal group of creditor countries – in the 1990s. According to analysis published in October 2022 by the African Development Bank, the 140 debt-for-nature swaps that took place between 1987 and 2003 accounted for a total of USD 1 billion, with a median value of about USD 25 million each, with the most credit-for-nature swaps made in the 1990s.

How debt-for-nature swaps could help South Asia

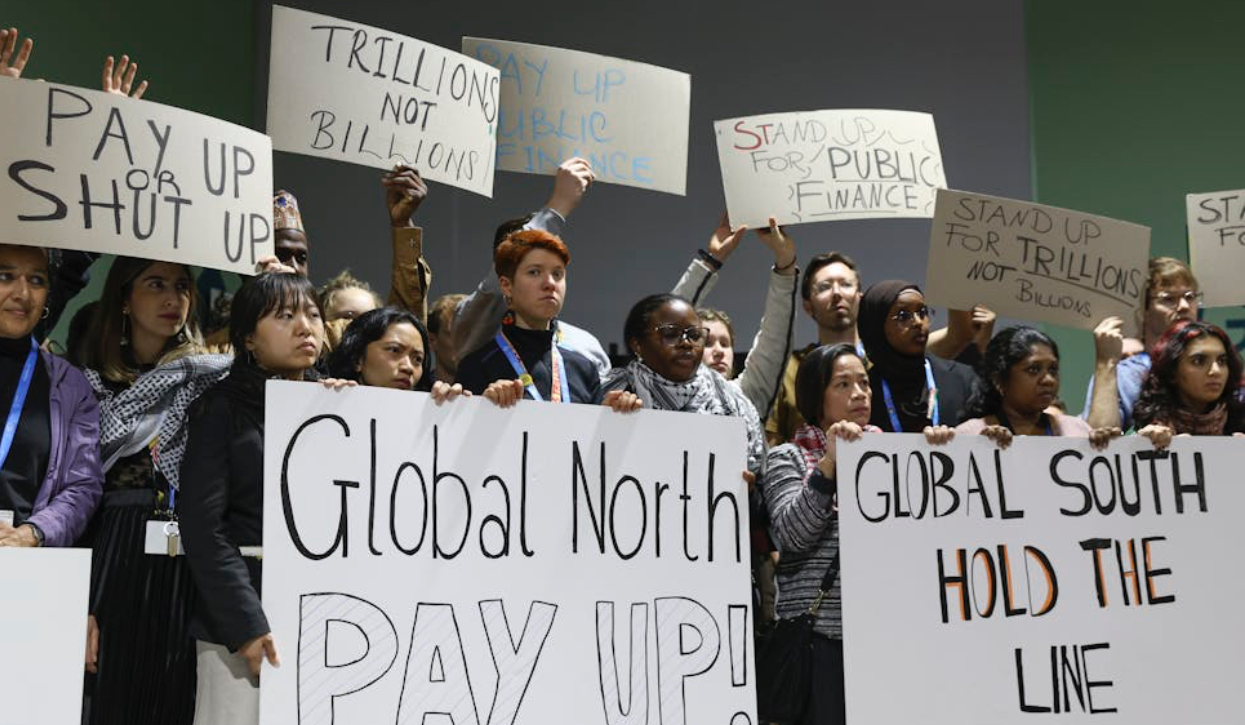

The debt crisis currently facing the Global South has highlighted the need for new solutions. Debt-for-nature swaps are seen by many actors – from governments and financial institutions to conservation organisations – as an important part of this. This is because developing countries face two interlinked problems. First, they need to borrow from international creditors to finance their development plans. Second, they must insulate, or adapt, their development to deal with the increasing impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss.

The scale of the challenge is striking in South Asia. Sri Lanka is still dealing with the impact of its poor financial management. Pakistan’s deeply indebted economy is struggling to recover from the 2022 floods, the cost of which is estimated at over USD 30 billion. While donors had pledged over USD 8 billion in aid, much of this has yet to be received. The Maldives, Nepal and Bangladesh are all struggling with rising food and housing costs, while India’s growth has slowed significantly.

Meanwhile, with the US Federal Reserve hiking interest rates, investments are flowing back into the United States. Developing countries have to contend with a stronger dollar, meaning the cost of repaying debt has increased. Researchers have calculated that “creditors will need to forgive up to USD 520 billion of the USD 812 billion in debt some 61 countries need to have restructured”.

The future for debt-for-nature swaps

The scale of the global debt crisis as well as the need for environmentally sensitive development make debt-for-nature swaps increasingly attractive, but there are major challenges to implementing them. The case of Belize’s 2021 debt-for-nature swap is illuminating in terms of what a deal can, and cannot, do. As Belize looked at a possible debt default or a highly austere loan, it reached a complicated deal with the Belize Blue Investment Company (created by NGO The Nature Conservancy) and Credit Suisse, through which it was able to wipe off some of its debt and instead issue ‘blue bonds’ to preserve its marine ecosystems.

While the deal helped Belize to avoid a painful financial decision, and certainly achieved investment in conservation, it only wiped away 12% of the country’s debt, at a price of USD 85 million in long-term transaction costs. Belize was still left with huge debts. Since debt-for-nature swaps are not part of normal financial institutional systems, the costs of insuring such transactions are high. Furthermore, credit agencies still regard them essentially as defaults, meaning the country’s credit rating gets downgraded, if not as much as in a full default.

A 2022 International Monetary Fund article notes that grants offer a simpler way of dealing with debt, stating that, “a swap cannot restore solvency [to a debtor country] unless it involves a sufficiently large share of a country’s debt and substantial relief… So far, no swap has come close to achieving this.” Furthermore, it seems contrary that a country should have to be at the point of economic collapse before a debt-for-nature swap is put in place, especially considering that if the developed countries that hold the debt, such as the members of the Paris Club, paid what they had pledged to developing countries in terms of climate finance, the debtor country might not have to be pushed to the brink of bankruptcy in the first place.

Despite these problems, the debt-for-nature swap market appears to be growing – Bloomberg estimates that it will reach USD 800 billion. This would go a long way towards reaching the goal of USD 4.3 trillion in annual financial flows by 2030 that think tank the Climate Policy Initiative estimates will be needed to offset the worst impacts of climate change. Protecting the natural environment remains one of the best way to combat those impacts, and debt-for-nature swaps could enable developing countries to do this while giving them fiscal space to pursue their development goals.

This story was originally published in The Third Pole.

Facebook Comments