‘The world has a week to ensure Nepal doesn’t move towards the catastrophic fate that we witnessed in India’

Just months ago, the world watched in horror as India was devastated by a second wave of Covid-19. Distressing images showed endless funeral pyres and the Ganges swollen with dead bodies, as desperate family members searched for their missing loved ones.

It was a visceral reminder of the deep disparity on which Covid-19 feeds and how inequalities aid its spread, its costs and its casualties.

The world now has a week to ensure Nepal doesn’t face the catastrophic fate that we witnessed in India.

Waiting for the second dose

More than 1.4 million people in Nepal, mostly over-65s, received their first Oxford-AstraZeneca doses of the Covid-19 vaccine in mid-March. Since then, supplies have dried up, forcing Nepal to extend the window for a second dose to 16 weeks. At the very latest, this group need a second dose before 5 July. Some need it as soon as the end of June.

But Nepal does not have the supply.

Missing this second dose could have far-reaching consequences. Those people risk not receiving a life-saving vaccine, and missing the deadline puts Nepal further behind in the race against Covid-19, which has toppled an already crumbling health system. Ultimately, millions of lives are at stake.

In May Nepal recorded one of the world’s highest infection rates, with the number of deaths doubling in just four weeks.

Nepal’s infrastructure, like that in India, is creaking under current caseloads, with dire shortages of oxygen, ICU beds, personal protective equipment and vaccines. Our recent Amnesty report paints a picture of chaos, as hospitals close their doors to new patients.

One doctor who spoke to Amnesty expressed it in the most poignant and painful terms. He said: “We have the collapse of human lives and no one will feel that pain – what remains is the suffering. We are helpless. It is so disrespectful. The dignity of human life is lost.”

Nepal has asked for help – we must answer

The international community has the power to help. Wealthy countries with large vaccine supplies, are in a position to provide much-needed assistance. It would be an affront to our collective moral conscience to let this happen again, when we already know how it ends. If your neighbour’s house is burning down, you don’t haggle over the garden hose. We are talking about their right to life.

The UK Government is one such player which could step in to provide assistance. Nepalese prime minister KP Sharma Oli has made a personal plea to the UK, as it’s “oldest friend”, to supply the vaccines it needs.

Britain and Nepal have a historically strong and enduring relationship. The UK is the biggest donor to Nepal, while tens of thousands of people of Nepali origin have formed vibrant communities across the UK. Thousands of Nepali Gurkhas still serve in the British Army.

Britain has large supplies of vaccines, having administered more than 70 million jabs to date, and ordered enough to vaccinate its population more than three times over.

The total of vaccines requested by Nepal represents just three days of the UK’s roll-out, or less than 0.3 per cent of its orders.

Nepal has only fully vaccinated 2.4 per cent of its population, while 45 per cent of the UK population has been fully immunised. As Nepal grapples to source basic medical supplies, the UK is looking to open up for mass events.

Sixteen British MPs from a number of parties have written to Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, criticising the Government’s lack of support to Nepal and urging it to provide urgent medical assistance, including vaccines. Celebrities including Sir Michael Palin and Joanna Lumley also recently signed a letter calling for increased medical support for Nepal.

But more pressure needs to be applied, and quickly. Time is running out.

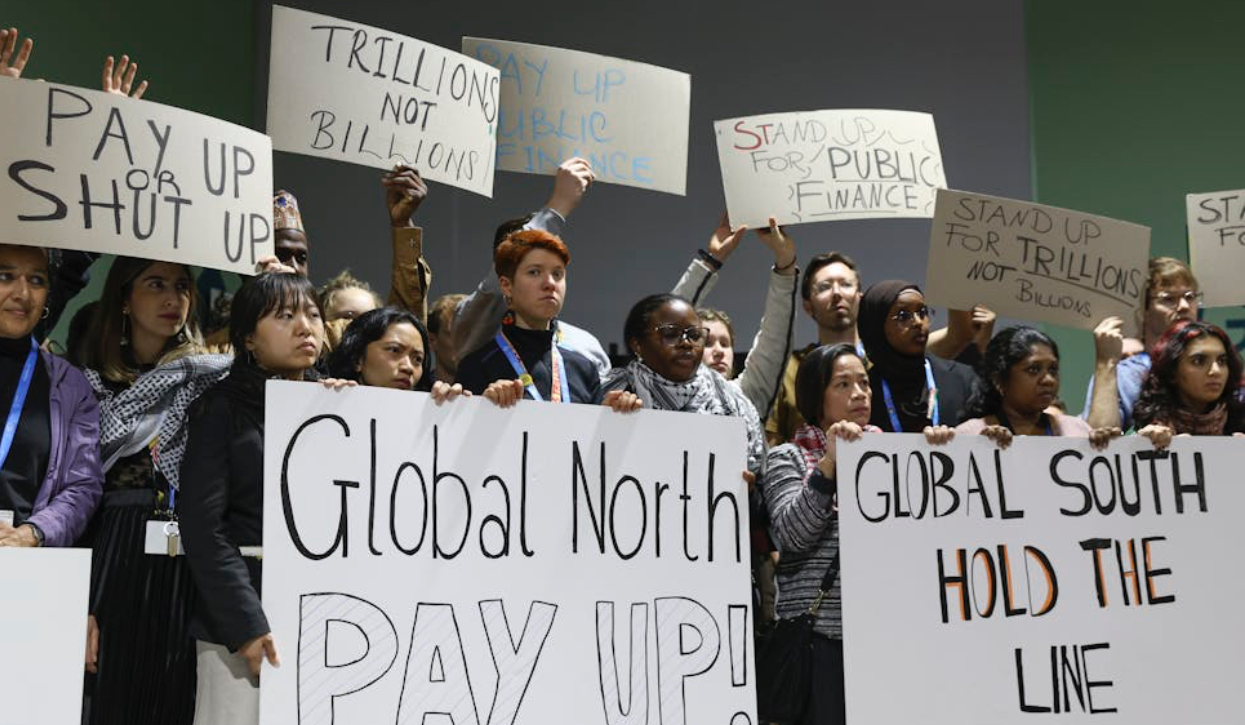

The crisis in Nepal is not the first and will not be the last. This pattern will continue as more poor countries around the world contemplate this very fate. It is a symptom of the scandalous levels of global vaccine inequality, fuelled by rich nations hoarding vaccines, and the refusal of pharmaceutical companies to share the rights and means to allow the world to produce more vaccines.

To save lives now, Prime Minister Boris Johnson can lead by example by immediately providing the doses needed to fully immunise 1.4 million Nepalis. This isn’t an unrealistic request – just weeks ago at the G7, Mr Johnson committed to sharing 100 million vaccine doses by the end of next year, 5 million of which should be shared by September.

To stop the crisis in Nepal from being endlessly repeated, he and other world leaders must also support moves at the World Trade Organisation to lift intellectual property restrictions on life-saving products, and push pharmaceutical companies to share their knowledge and technology. Leaders must realise that viruses don’t care about borders. This is a global issue that requires urgent global action now. ( This article was originally published in iNews)

Agnes Callamard is the Secretary-General of Amnesty International

Facebook Comments