Nepal said to be vulnerable to the deadly disease glanders

From : Horsetalk

Nepal is said to be at risk of an outbreak of the deadly disease glanders, which would seriously affect the welfare of equines and the livelihoods of many poor families.

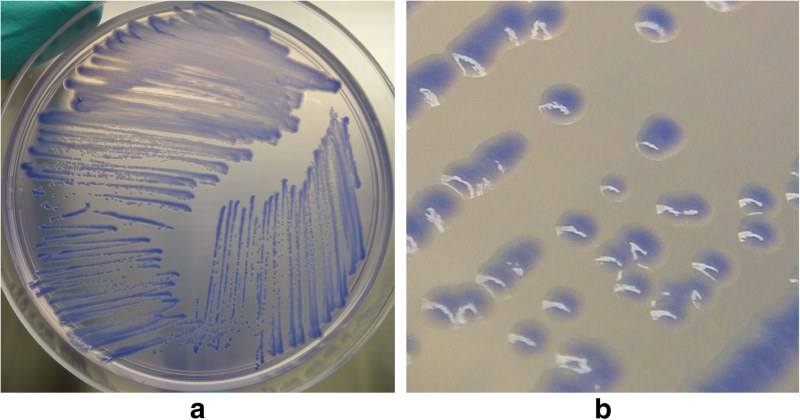

Glanders, which is usually fatal to both animals and humans, is caused by the bacterium Burkholderia mallei.

It affects mainly horses, mules, and donkeys. Signs include lung lesions and ulceration of mucous membranes in the respiratory tract. The acute form results in coughing and fever, followed by septicaemia and death within days.

Niran Adhikari, Krishna Prasad Acharya and Richard Trevor Wilson, in a letter to the journal Tropical Medicine and Health, say an outbreak is a distinct possibility in the short term.

This is due to its re-emergence in India and periodic unrestricted migration of equines from there, especially from neighboring Uttar Pradesh, where 89 outbreaks were reported in 2017.

The trio say confirmation of glanders has not been possible in suspected cases submitted by field veterinarians in Nepal, mainly due to the lack of diagnostic tools.

outbreak, they say, would affect rural, marginalized communities and the brick kiln industries, in which more than 2200 of Nepal’s 56,834 equines work.

“Brick-making is one of the largest employers of human labor in the country. An outbreak of glanders would thus have an enormous negative impact not only on the horses but also on the poor people who work with them and have no possibility of other forms of employment.”

More attention by the government to the disease is warranted, they say. A strengthened animal quarantine system with holding yards and laboratory backups were required.

Nepal currently has eight quarantine offices and 29 animal quarantine check-posts.

The nation imported 2690 equines from India in 2017.

“Most equines imported from India passed through the Nepalgunj quarantine office, the closest to India’s Uttar Pradesh region.

“Quarantine officers can prohibit entry of animals from such disease-outbreak regions but poor coordination with Indian quarantine check posts, lack of animal holding yards, and illegal migration through the open border create problems for the Nepalese quarantine service.”

Nepal’s Central Veterinary Laboratory is the national veterinary reference laboratory. Samples from suspicious imported animals are dispatched there for analysis, but it does not have the facility to test for glanders.

The high cost of the preferred test for the bacterium means it is less affordable as a screening test for low-income countries such as Nepal, the trio say.

“No confirmed cases of glanders have so far been identified but the threat of the disease being introduced is very real in view of the weak surveillance and animal quarantine activities.”

For now, the authors say quarantine offices should keep full records of equines imported from outbreak regions and possibly even prohibit their entry.

Where equines are allowed into the country, a simpler and more affordable screening test should be applied.

They say the long-term goal should be to improve coordination between quarantine offices on both sides of the border zone. Stringent quarantine measures should be enforced and equines in Nepal should be tested for the disease, with positive cases euthanized.

They proposed a campaign to improve awareness of the disease.

Adhikari is with Animal Health Training and Consultancy Services, in Pokhara, Nepal; Acharya is with the Animal Quarantine Office in Budhanilkantha, Kathmandu, Nepal; and Wilson is with Bartridge House in Umberleigh, Britain.

Adhikari, N., Acharya, K.P. & Wilson, R.T. The potential for an outbreak of glanders in Nepal. Trop Med Health 47, 57 (2019) doi:10.1186/s41182-019-0185-2

Facebook Comments